Portfolio Magazine

New from Nowhere?

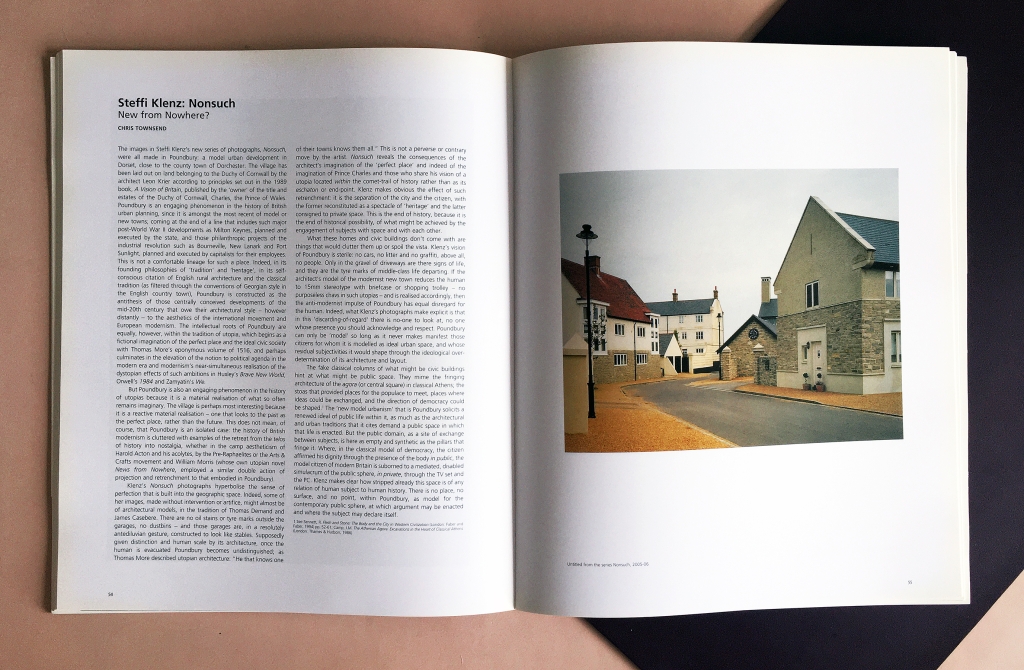

The images in Steffi Klenz’s new series of photographs, Nonsuch, were all made in Poundbury: a model urban development in Dorset, close to the county town of Dorchester. The village ahs been laid out on land belonging to the Duchy of Cornwall by the architect Leon Krier according to the principles set out in the 1989 book, A Vision of Britain, published by the ‘owner’ of the title and estate of the Duchy of Cornwall, Charles the Prince of Wales.

Poundbary is an engaging phenomenon in the history of British urban planning, since it is amongst the most recent of model or new towns; coming at the end of a line that includes such major post-World War II developments such as Milton Keynes, planned and executed by the state, and those philanthropic projects of the industrial revolution such as Bourneville, New Lanark and Port sunlight, planned and executed by capitalists for their employees.

This is not a comfortable lineage for such a place. Indeed, in its founding philosophies of ‘tradition’ and ‘heritage’, in its self-conscious citation of English rural architecture and the classical tradition (as filtered through the conventions of Georgian style in the English country town), Poundbury is constructed as the antithesis of those centrally conceived developments of the mid-20th century that owe their architectural style – however distantly – to the aesthetics of the international movement and European modernism. The intellectual roots of Poundbury are equally, however, within the tradition of utopia, which begins as a fictional imagination of the perfect place and the ideal civic society with Thomas More’s eponymous volume of 1516, and perhaps culminates in the elevation of the notion of political agenda in the modern era and modernism’s near-simultaneous realization of the dystopian effects of such ambitions in Huxley’s Brave New World, Orwell’s 1984 and Zamyatin’s We.

But Poundbury is also an engaging phenomenon in the history of utopias because it is a material realisation of what so often remains imaginary. The village is perhaps most interesting because it is a reactive material realization – one that looks to the past as the perfect place, rather than the future. This does not mean, of course, that Poundbury is an isolated case: the history of British modernism is cluttered with examples of the retreat from the telos of history into nostalgia, whether in the camp aestheticism of Harold Acton and his acolytes, by the Pre-Raphaelites or the Arts & Crafts movement and William Morris (whose own utopian novel News from Nowhere, employed a similar double action of projection and retrenchment to that embodied in Poundbury).

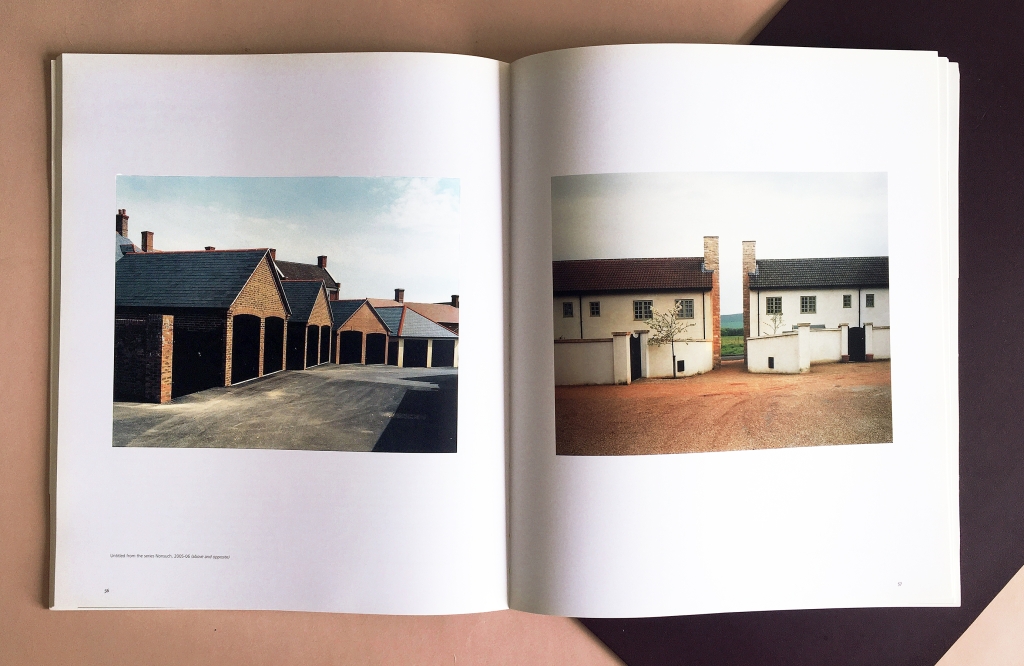

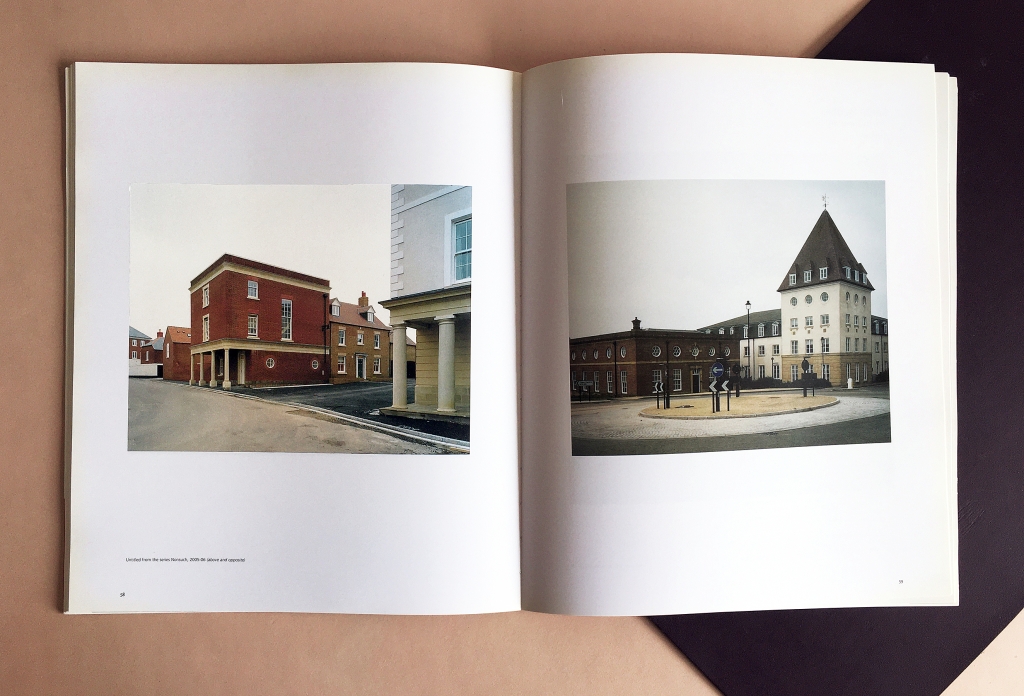

Klenz’s Nonsuch photographs hyperbolise the sense of perfection that is built into the geographic space. Indeed, some of her images, made without any intervention or artifice, might almost be of architectural models, in the tradition of Thomas Demand and James Casebere. There are no oil stains or tyre marks outside the garages, no dustbins – and those garages are, in a resolutely antediluvian gesture, constructed to look like stables. Supposedly given distinction and human scale by its architecture, once the human is evacuated Poundbury becomes undistinguished; as Thomas More described utopian architecture: “He that knows one of their towns knows them all.” This is not a perverse or contrary move by the artist. Nonsuch reveals the consequences of the architect’s imagination of the ‘perfect place’ and indeed of the imagination of Prince Charles and those who share his vision of a utopia located within the comet-trail of history rather than as its eschaton or end-point. Klenz makes obvious the effect of such retrenchment: it is the separation of the city and its citizens, with the former reconstituted as a spectacle of ‘heritage’ and the latter consigned to the private space. This is the end of history, because it is the end of historical possibility, of what might be achieved by the engagement of subjects with space and with each other.

What these homes and civic buildings don’t come with are things that would clutter them or spoil the vista. Klenz’s vision of Poundbury is sterile: no cars, no litter, no graffiti, above all, no people. Only in the gravel of driveways are there signs of life, and they are the tyre marks of middle-class life departing. If the architect’s model of the modernist new town reduces the human to 15mmstereotype with briefcase or shopping trolley – no purposeless chavs in such utopias – and is realized accordingly, then the anti-modernist impulse of Poundbury has equal disregard for the human. Indeed, what Klenz’s photographs make explicit is that in this ‘discarding-of-regard’ there is no one to look at, no one whose presence you should acknowledge and respect. Poundbury can only be a ‘model’ so long as it never makes manifest those citizens for whom it is modelled as an ideal urban space, and whose residual subjectivities it would shape through the ideological over-determination of its architecture and layout.

The fake classical columns of what might be civic buildings hint at what might be public space. They mime the fringing architecture of the agora (or central square) in classical Athens; the stoas that provided places for the populace to meet, places where ideas could be exchanged, and the direction of democracy could be shaped. The ‘new model urbanism’ that is Poundbury solicits a renewed ideal of public life within it, as much as the architectural and urban traditions that it cites demand a public space in which that life is enacted. But the public domain, as a site of exchange between subjects, is here empty and synthetic as the pillars that fringe it. Where, in the classical model of democracy, the citizen is affirmed his dignity through the presence of the body in public, the simulacrum of the public sphere, in private, through the TV set and the PC. Klenz makes clear how stripped already this space is of any relation of human subject to human history. There is no place, no surface, and no point, within Poundbury, as a model for the contemporary public sphere, at which argument may be enacted and where the subject may declare itself.

Chris Townsend is an independent art historian and art critic. He is the Head of the Media Arts Department at Royal Holloway, University of London and regularly writes for the magazine Art Monthly.

(This text was firstly published in the magazine Portfolio, Issue 43, 2006, UK and USA)